The power of letter-writing

The power of a letter in a crisis and beyond by mentor Clare Lewis

….like someone extending their hand out, reaching across a divide

In the current Covid-19 lockdown, a hand of friendship in the form of a letter could be an extremely simple and effective way for mentors to help break through the visible and invisible walls of isolation that surround their mentees. Especially if they are in prison.

For the past three years, I have had the privilege of mentoring James (as I am going to call him here), a talented and hardworking Longford Scholar studying inside for an OU degree. The opportunities for face-to-face meetings at the two prisons he has been in so far are limited – I aim to visit once an academic term – and digital forms of contact are not an option. Although the prison education officers are responsive to emails and willing to act as go-betweens, I feel it’s not fair to take advantage of their good nature. So, in order to maintain more regular and specific contact with James, I have taken to letter-writing.

In the footsteps of history...

We are following a path starting in Ancient India, Ancient Egypt through Rome, Greece and China. Archives of correspondence, whether for personal, diplomatic or business reasons, are also an invaluable primary source for historical research. In the 17th and 18th century letters were used to self-educate as well as offering the opportunity to practice critical reading, self-expressive writing, polemical writing, and the exchange of ideas with like-minded others.

One of the first novels, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, was composed entirely of letters by a daughter to her parents, the epistolary method giving the novel its sense of realism. In today’s digital world letters tend to be the generated by computer, written for business reasons and arrive in brown envelopes. A handwritten letter is a luxury.

A unique personal touch….

I initiated my letter-writing with much more humble ambitions – a desire to let James know that I was thinking of him and supporting him, albeit not in person. I can only imagine how much motivation it takes to knuckle down to work when you are remote learning. Fortunately, he is an incredibly self-motivated scholar and probably doesn’t need prompts, but I hoped that a letter would help him feel connected to the wider world and more specifically to the Longford Trust network.

Whatever the intention, the impact of a letter, however brief or mundane, cannot be overestimated. A letter is capable of generating a tangible feeling. It’s as if someone has extended their hand out and reached across a divide. It is akin to a person actually being in a room with you.

Letters are also powerful tools to convey kinship and thoughtfulness. The idea that someone has taken time out of his or her day – everyone has other stuff to do – to sit down and write, find an envelope, look up the address, get a stamp and finally post it can really boost how someone feels and lift a mood. The words go way beyond what is actually written on the page bringing the writer’s personality and voice to life, similar to reading a novel where it’s possible to create a whole visual picture as you read.

What to talk about ….

Like everyone, I can find a blank piece of paper daunting. Have I got anything interesting to say? Can I express myself well enough? What should I talk about? What would James like to hear about? But I’ve decided it is better to not worry about these things and just write, unfettered by any worries of whether it is going to be good enough, long enough, interesting enough.

It almost doesn’t matter in the end. It’s the thought that counts and the sentiment it conveys. Having said that, James does write a very accomplished letter, so I do try hard to match his eloquence!

In the context of writing to James I am sometimes unsure if I am bound by any rules of what might be considered suitable topics of conversation. Are letters subject to censorship? Can I include press cuttings? But I am confident the team at the Longford Trust can answer any questions I might have.

PS Don’t forget…..

Before writing this blog, I asked the team if they had any advice. Jacob Dunne, who moderates the trust’s secure online platform for scholars and mentors (contact him at slack@longfordtrust.org to find out more), made the excellent point that obtaining stamps can be a problem for inmates. So from now I will include a stamp in any letter I write to James.

However, I am conscious that when I write I don’t expect a response. It is something done for its own sake. So I will always include a proviso that the stamp can be used for someone else.

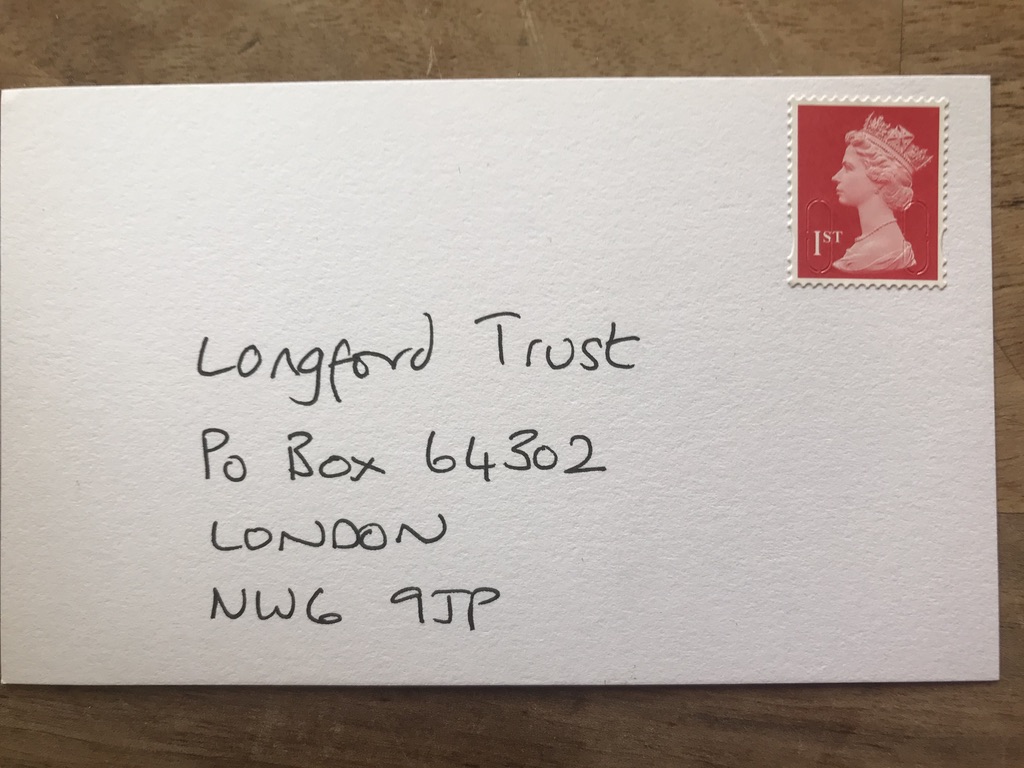

If you are a scholar or mentor keeping in touch by letter we provide a confidential forwarding service through our PO Box address: Longford Trust, PO Box 64302, London, NW6 9JP. We recommend letters to scholars in prison include a stamped addressed envelope.