The trick is to realise that it is for you

Longford Scholar, Darren Robert, has just graduated in scriptwriting from the National Film and Television School. Today he is in the running for a dream job at the BBC. Here, he traces it all back to prison and daring to believe that higher education could be for someone like him – and someone like you.

There are a few things in my life that have been consistent; my mom, brother and sisters (except when my mother kicked me out), the neighbourhood I grew up in, the friends I had from that neighbourhood, being broke, and the feeling that somehow, I was going to make it out and everything would be okay. For a long time, I thought music would be that way out, but after getting locked up again at 25, after just being released at 25, whilst in the midst of working on my mixtape, I thought this music thing might not work out.

Crime was never really something I wanted to do; it was just something I fell into. Even while I was making money serving the local addicts, I didn’t really care for it. Knowing I wouldn’t be let back into the free world until the age of 28, I felt like that would be too old start all over again. Whilst lying on the top bunk letting my mind wonder, something that had been pushed to the back of my mind for some years came to the forefront. I watched my early life play out like the opening to a TV show; the journey back home from church late on a Sunday night, driving through the bleak run-down street known for prostitution that leads into my neighbourhood right next to the vicarage with the wall spray painted ‘Give me life, give me a job pop’. I always wondered who pop was, and what kind of jobs he had to offer. The whole thing became so clear to me.

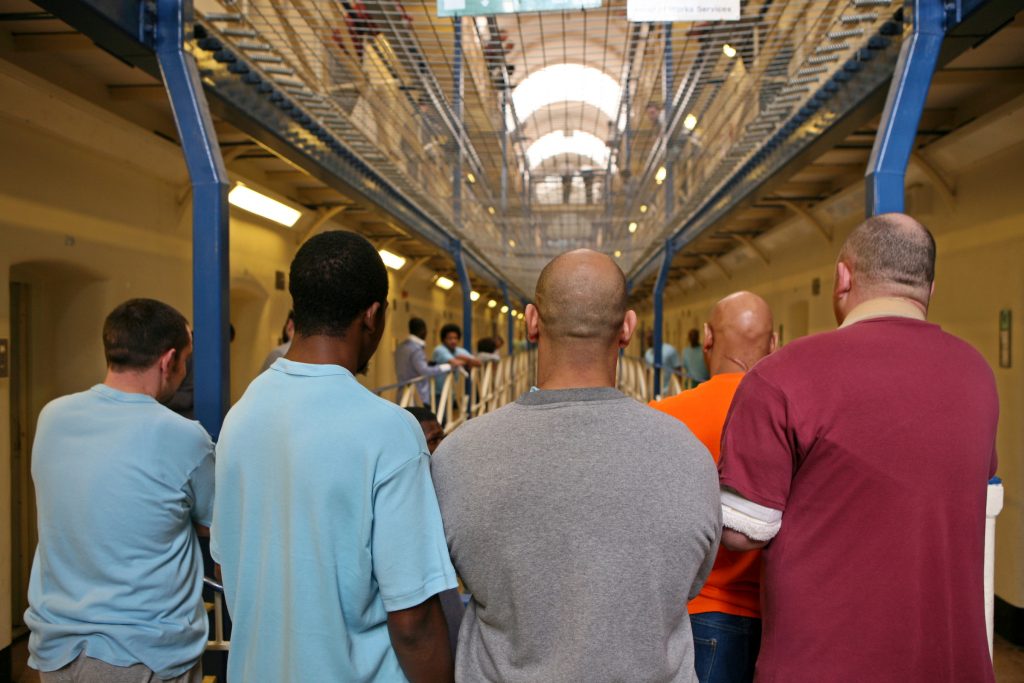

At that moment I decided that I was going to write TV. But I had no idea what I was doing. I just got a sheet of A4 lined paper, wrote names in the margin and wrote dialogue. I didn’t realise I had to set the scene, or how I was supposed to lay it out. After refusing to go to education in the prison for a few weeks, as I knew I could get an extra gym session instead, the officers told me I’d be going on basic if I didn’t get down there.

‘You shouldn’t be here, you should be in university.’

So, I went down, not wanting to lose my TV, and was put into an English class. English was pretty much the only thing I was good at in school academically, though my grades didn’t prove that. When I was young my mom would make me stand in front of the heater and do my spellings while she grilled me from the settee. So, I guess I owe my reading and writing skills to her.

In this English class on this one day that I went down to education, there was a substitute teacher from the Open prison across the road. Real nice lady, very smartly dressed, I even noticed the classy Rolex she had on. She gave me a piece of work to do, which was to read a paragraph, and then write a paragraph about it. I don’t remember what it was I read or wrote but I remember her reaction to it. ‘Ughh, with writing like this you shouldn’t be here, you should be in university!’

It was strange to hear knowing that my schoolteachers most likely felt I was exactly where I belonged. I felt very encouraged by her response, and in my head, I was thinking,‘funny you say that, I was just thinking about being a writer.’

I never saw her again after that day, but I consider her a guardian angel who came to point me in the right direction. I was shipped out a few days later to a Cat C prison. When the education people came to see me about what I’d like to do whilst at their establishment, I said, ‘I want to get into screenwriting’. I didn’t think that would be something the prison would offer but I had heard about Open University and hoped there may be something I could do through them.

Plus, I thought if I could do something like that, it would keep officers off my back about going to work. The lady found me a course with Stonebridge Associated Colleges in Scriptwriting for Film, TV, Stage and Radio. I also found in the prison library two sheer assets for what I wanted to do; Teach Yourself Screenwriting, and the script in book form to Reservoir Dogs, one of my favourite films. I’ll be honest, I took the books from there and kept them for myself until I was released, because I just knew that I needed them more than anyone.

‘Me of all people, an A+, I couldn’t believe it’

When the work started coming through, I got straight to it. I put up pictures of Bafta and Oscar awards in my cell for motivation (and also manifestation) and knuckled down, although it took me a lot longer to get work done as I was writing scripts by hand and learning as I went along. The tutor was very forgiving with the time I was taking, and as there were no deadlines. I didn’t feel pressured. He also seemed to like my work. I sent the last piece of work off after my release in 2016 and was ecstatic when they sent me back a diploma with an A+ grade. Me of all people, an A+, I couldn’t believe it. But I didn’t want to stop there. I wanted to continue learning. I just knew for certain I was on the right path this time. I looked up local university courses and finally settled on Creative Writing and Film and TV Studies at Wolverhampton University, where I started in September that year.

I had never written essays before and struggled with the academic side of things, but creatively I was doing well. I was learning the craft quickly and got praise for it by my tutors. But this was mostly in the form of short stories. There wasn’t much actual screenwriting going on. Having had to repeat a year as I lacked in some work, my final year was from 2019-2020. By this time, I had grown slightly bored of the course, as it wasn’t specific to what I wanted to do. A friend and mentor of mine that I had met on a media course whilst inside had told me about the National Film and Television School and said that’s where I needed to be. He said that’s the cream of the crop. It’s where shows like Eastenders come and cherry pick their writers. He said you go there, and you complete the course, and they give you an agent. I thought I should check it out.

‘I feel like I know who I am again, and where I’m going’

I had some mental pushback, believing that a school like that probably wouldn’t want someone like me, but when I went down for the Open Day, I saw an actual Bafta and an actual Oscar award in the flesh, and I was immediately sold! I knew I had to be here. I completely forgot about the undergrad and focused on the NFTS. It was risky, as the course only accepts 10 people per year, but I didn’t care. I filled in the long application form and attached a pilot script I had written and sent it off. On my birthday that year in July, I got the email saying I was accepted, and I was over the moon. But in December I was arrested again, and in January I was sent to prison for 6 months. I was due to start in February. I was gutted. I thought it was over. But the school stood by me and allowed me to defer. I started in 2022, made the move to Buckinghamshire and got to work. I had no idea how I was going to pay for the course, or my living, but luckily landed a scholarship from the BBC which covered it.

Two years and some change later, I am now a Master of Arts, Film and Television, I have an agent and I am in the running to work on a high-level TV show. None of this could have been done without all the help along the way from tutors who work to see people making use of their talents. Ever since I made that decision to start writing, I’ve felt like I know who I am again, and where I’m going. It hasn’t been easy, but it’s definitely been worth it, and now I can look forward to the future.

I truly believe that education is the key. The trick is to realise within yourself that it is for you too. Don’t believe what you’ve been made to believe your entire life, that you belong in a box, mentally or physically. Education can and will open your mind and your life to new realities, and you can bring forth the positive lifestyle change that you desire.

Don’t be afraid, make the decision.

If you believe you could do a university degree, too, contact Clare Lewis, the Longford Trust’s scholarship manager to find out how.