Isolation: an expert survivor’s guide

Isolation: an expert survivor’s guide by artist and former Longford scholar Lee Cutter

I know a bit about isolation. In fact, after three years in prison I am an expert. Through this coronavirus crisis people keep asking me, ‘What’s it like in isolation? How do you cope?’ as they deal with anxiety and worry about separation from friends, colleagues and family. Everyone is searching for reassurance and tips to cope with curtailed freedom, albeit at home.

It’s got me thinking.

They say your first day in prison is the toughest. For me it came about six months into my sentence. The first day in a young offenders prison was certainly confusing and a struggle, my whole understanding of the world feeling flipped upside down, but I still had some freedom, as prison goes. This was because I was on remand, waiting for a judge to sentence me. I could work, attend classes in education, mix with others in prison – ‘associate’ as they call it inside, and go to the gym.

Just a few months on, I started to understand the environment, in an odd way, I felt part of a community. Then I was sent to Crown Court to receive my sentence. At that time, the now thankfully abolished indeterminate sentence was popular. It was a lottery whether I’d get one, carrying the real fear of never knowing when I might ever be free again. But my case was adjourned, pushed to another date. It was in the next, different young offenders prison where the pain of isolation really hit.

In limbo, I spent days and months on end in a single cell with only myself for company, locked up for 24 hours a day, with access to two phone calls and two showers a week. The prison was overcrowded, understaffed, and those under 18 were given priority to work and education. I was unlucky I was 18 years old. Though looking back, my mind felt a lot younger and I had never experienced anything like this before.

In the first few weeks I distracted myself with the television and the radio, anything to get a sense of a world beyond my four walls. During the day I’d talk with my next-door neighbour through the gap in the pipes at the end of the cell. It was at night I’d struggle with my thoughts. It’s an understatement to say the next few months were a challenge. I’d think, and think, and think. I’d think about the mistakes I had made, how they had affected people, I’d think about my family, the events that led to my situation. I wondered if it would be like this forever. It was sending me crazy. I knew I had to change, and that I’d need to teach myself how.

And then an unexpected opportunity presented itself – a pencil.

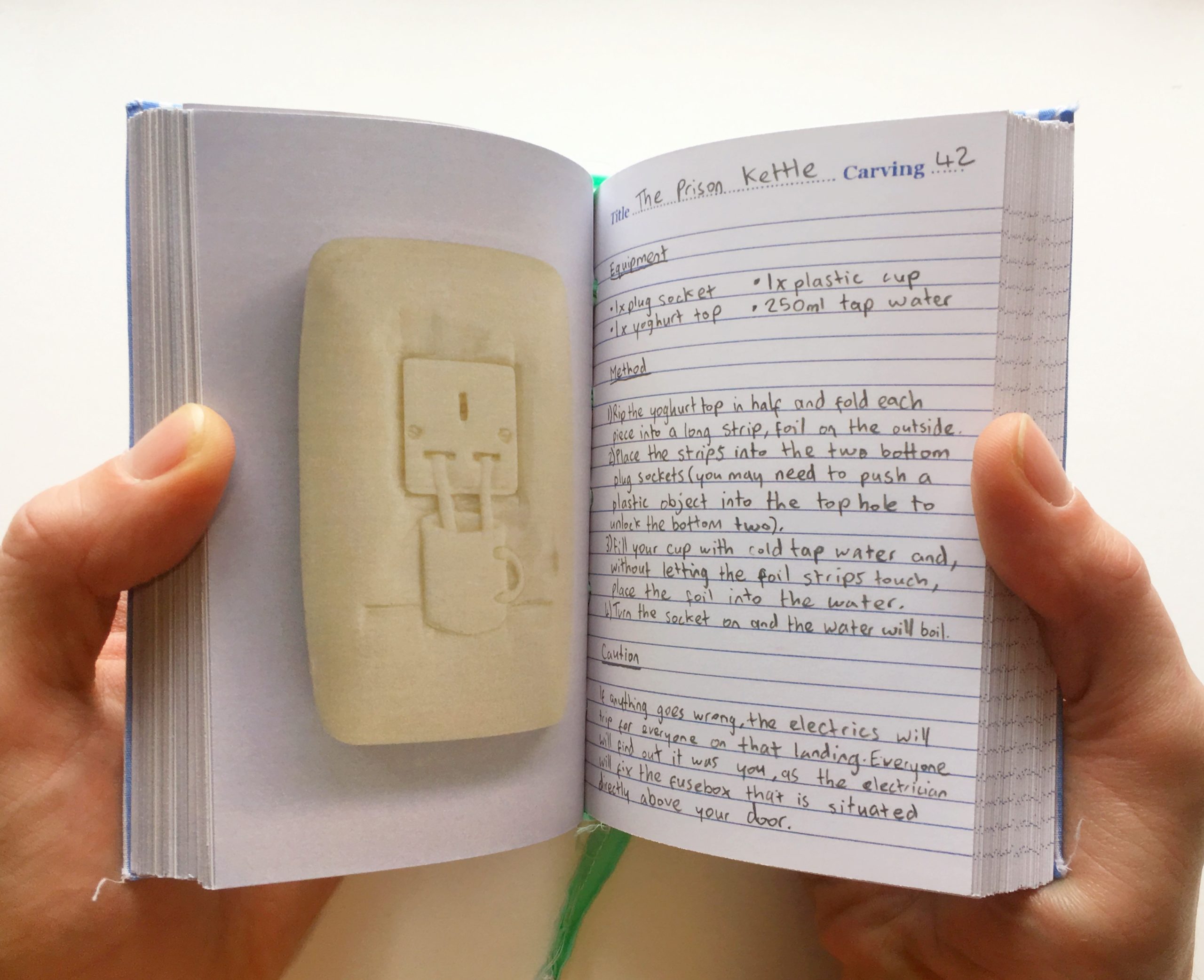

An officer had left a pencil in my cell by accident, I used it to write down my thoughts and feelings onto any scrap of paper I could gather. It took the negative thoughts out of my head, and by seeing them in front of me, it somehow helped me to understand where they might have come from, how I could change them. I began making drawings of my cell, I’d draw the sink, the bed, the window, anything in front of me. When I ran out of paper, I would draw into bars of standard prison issue soap. The soap was free on the wing and it was much more accessible than a piece of paper.

Funnily enough, I didn’t see myself as an artist, I found a creative side within me. I didn’t know anything about art, I don’t even think I liked art much at the time but I knew that making was helping me.

A few months later I was sentenced, avoiding the dreaded indeterminate sentence. This time I moved prisons again. In the new prison I had access to more arts materials, more time out of my cell. Officers and other inmates saw my drawings and soon started to give me photographs of their loved ones and pets to draw. They’d ‘pay’ me in toiletries and food. Looking back, I guess these were my first commissions.

It’s odd thinking back to those times. It feels like a different me then, and yet those times, and the isolation, have contributed to the person and the artist I am today. I’ve been out of prison for ten years now, have completed a BA degree in Fine Art, with support from the Longford Trust, got a postgraduate at the Royal Drawing School. I now have a much sought-after job with Koestler Arts – encouraging people in prisons and other secure settings to engage in the arts. I am proud to say I have achieved what many artists never manage, exhibiting in the prestigious Royal Academy, Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, Christie’s, the upmarket auction house and the Royal Festival Hall. And I am now a mentor for an artist through the Longford Trust who is studying a distance -learning degree in prison. I often think about what life is like for him being creative in his prison, I can see confinement shapes his work.

As we all face the isolation of coronavirus and restrictions in our daily lives and relationships I wouldn’t wish this uncertain period of confinement on anyone. One silver- lining is perhaps the insight it offers, a window into imprisonment. The lack of control, unable to go out when you feel like it, prevented from learning in a classroom or library when you choose, no longer seeing or hugging a grandparent –the punishing impact of not doing what used to be normal. I hope and trust we will all dig deep in this coronavirus, finding some hidden talents – as myself and my mentee have done with art. Spare a thought for the 80, 0000 plus men, women and children in overcrowded, often dirty prisons across England and Wales who know isolation and resourcefulness all too well. Next time someone says prison is too ‘soft’ remember this time and remind them what it felt like during the coronavirus crisis.

Find out more about Lee and his hand-made book An Inside Story, a hand bound with prison bedsheets and visitation shirts here: https://www.koestlerarts.org.uk/shop/books/an-inside-story/