Reduce Demand for Prisons, Not Meet It

Longford Scholar Chris Walters (currently working at the Trust’s Fundraising Manager) shared some reflections on October 22 with readers of the Independent in a personal Comment article for the paper about the plans the government has announced to cope with the overcrowding crisis in prisons. Drawing on his own experiences, Chris questioned whether the proposals will actually ease the problem. We are sharing the article here, with thanks to the Independent.

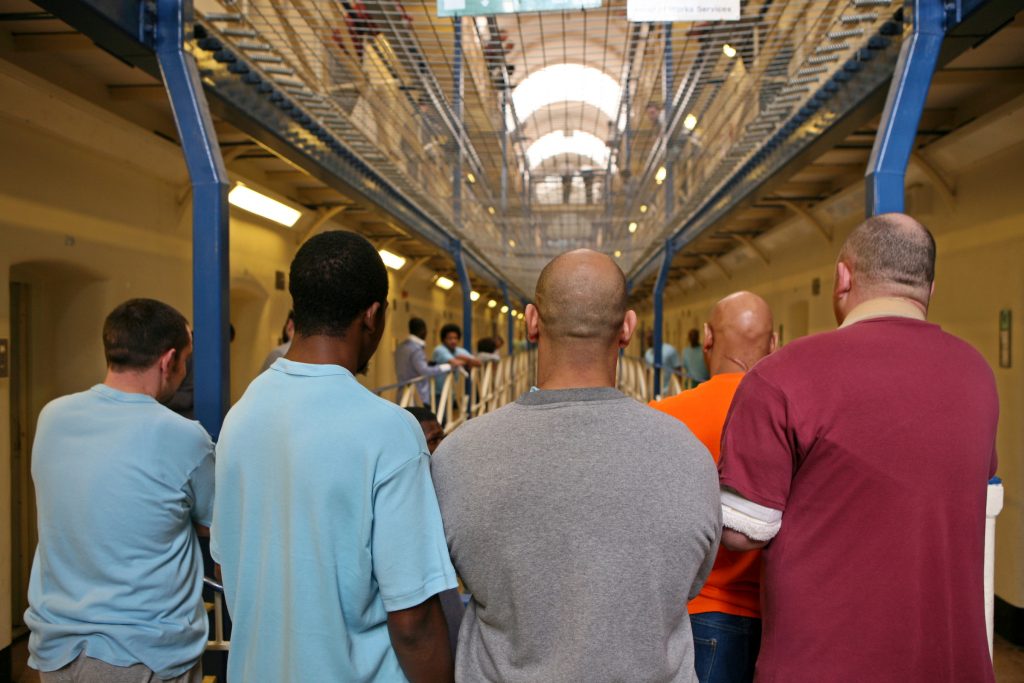

With the government’s latest plans to address our prisons crisis – the jail population is at an all-time high, with as few as 550 spare places left in the system – justice secretary Alex Chalk asks us to believe the unbelievable. He cites Covid-19 and industrial action as the significant pressures filling up our prison estate. But even in 2015, 60 per cent of our jails were overcrowded.

Again, Mr Chalk lauds his government’s efforts to return offenders on parole who breach their licence conditions to prison, even if it contributes to overcrowded jails as if this didn’t happen before, and isn’t indicative of wider failures in the criminal justice system

Criminals are “dangerous” – except for the ones the government has earmarked under its proposals to free up capacity: those convicted of less serious offences who warrant early release, and those minor offenders being spared a jail term altogether. It is a plan that belies a wilful misunderstanding of the criminal justice system.

‘I’ve witnessed swarms of rats, tried to keep clean in filthy showers, and in 2018, during the freezing Beast from the East, I worried I wouldn’t survive the night as icy wind blew in through the broken window.’

I served two years in prison, from 2018 to 2019 – first at HMP Wandsworth, and then at HMP Ford. Despite what Mr Chalk may believe, there aren’t spacious single cells just waiting to be transformed into doubles. Shoving more prisoners into a cell is hardly a solution to an overcrowding issue. The bleached bones of the UK prison estate have long been picked clean by ambitious ministers just like him who demand that prison governors find more capacity.

And what are these non-essential maintenance works which Mr Chalk says have now been stopped, thereby opening up more cells for use? From all accounts, our prisons are run-down and unhygienic. I’ve witnessed swarms of rats, tried to keep clean in filthy showers, and in 2018, during the freezing Beast from the East, I worried I wouldn’t survive the night as icy wind blew in through the broken window.

All the while prisoners and staff are battling for survival, they don’t have the capacity to work on rehabilitation. And so, when prisoners are released, they often return – and so the prison population rises, and the government responds with a vow to get tougher on crime and builds more prisons.

Meanwhile, there is a growing number of prisoners on remand, not yet convicted of a crime, which is an indication of a wider problem in the criminal justice system. There is a severe backlog of criminal cases – some people are now waiting five years for a trial date – and the government’s insistence on locking people up for longer will not help.

Mr Chalk crassly described the proposed growth in the prison estate as meeting demand, but it’s more apt to say it is feeding a fire. Until there is ground-up radical reform, we will have this same conversation again and again and again.

People on remand are held in prison conditions so poor that two separate European nations have recently refused to extradite people to this country if they face imprisonment. The justice secretary has proposed to increase the sentence discount for people who plead guilty. He said this is to “[…] encourage people to plead guilty at the first opportunity”. Those on remand are presumed to be innocent, and when held in such poor conditions, it is especially unjust and immoral for him as the Lord Chancellor – upholder of our legal system – to coerce them into pleading guilty.

‘It doesn’t matter how good your education programme is if prisoners are confined to their cells for most of the day in overcrowded jails’

The government has given some ground, it seems, almost begrudgingly. Mr Chalk has described Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentences as a “stain on our justice system”, and yet only pledges to implement one of the 22 recommendations found in the report by parliament’s Justice Committee, which examined IPP sentences. Further use of community orders and a reduction in short custodial sentences are welcome, but don’t “grasp the nettle”, as Mr Chalk puts it. Most prisoners are serving custodial sentences of over a year and won’t be affected. Moreover, these plans put further strain on services inextricably linked to the prison system such as probation, healthcare and housing. It will inevitably be charities who pick up the slack.

Actual long-term reform gets short shrift from Mr Chalk. He has pledged that prisons will be “geared to help offenders turn away from crime, to change their ways, and become contributing members of society”. But he says nothing about how that is to be achieved.

Prisons minister Damian Hinds has rightly recognised the importance of education in reducing reoffending, promising a brand new Prison Education Service. This is a great move, but meaningless unless the issue of offending is addressed holistically. It doesn’t matter how good your education programme is if prisoners are confined to their cells for most of the day in overcrowded jails.

‘We can reduce the demand for prisons by meeting the needs of our people’

The government is well aware that the most important factors in reducing reoffending are education, employment, housing and maintaining family ties. Yet it seems they are more concerned with increasing the quantity of their prisoners than the quality of their prisons. A quality prison should reduce the prison population, as we have seen in Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands.

The justice secretary should seek to reduce demand for prisons by lobbying in cabinet for wider reform. Prison staff and Legal Aid solicitors’ pay must reflect the important role they play in our society. Prisons must meet minimum basic standards to ensure prisoners re-enter society with dignity. The National Health Service must expand and receive more funding to better address mental health issues in the community. The government must do more to prevent homelessness and poverty.

Overcrowded prisons do not exist in a vacuum separated from the other pressures on society. They are the result of inadequately addressing those pressures. We can reduce the demand for prisons by meeting the needs of our people.